Prostate Cancer Treatment

General Information About Prostate Cancer

Key Points

- Prostate cancer is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in the tissues of the prostate.

- Signs of prostate cancer include a weak flow of urine or frequent urination.

- Tests that examine the prostate and blood are used to diagnose prostate cancer.

- A biopsy is done to diagnose prostate cancer and find out the grade of the cancer (Gleason score).

- Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options.

Prostate cancer is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in the tissues of the prostate.

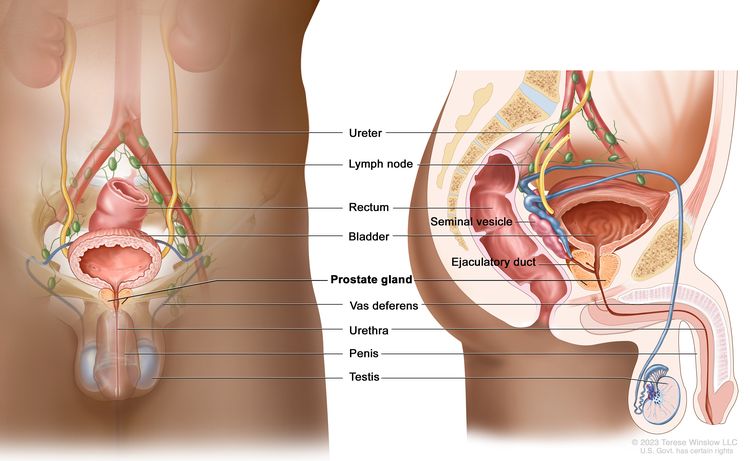

The prostate is a gland in the male reproductive system. It lies just below the bladder (the organ that collects and empties urine) and in front of the rectum (the lower part of the intestine). It is about the size of a walnut and surrounds part of the urethra (the tube that empties urine from the bladder). The prostate gland makes fluid that is part of the semen.

Prostate cancer is most common in older men. In the U.S., about 1 out of 8 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Signs of prostate cancer include a weak flow of urine or frequent urination.

These and other signs and symptoms may be caused by prostate cancer or by other conditions. Check with your doctor if you have any of the following:

- Weak or interrupted ("stop-and-go") flow of urine.

- Sudden urge to urinate.

- Frequent urination (especially at night).

- Trouble starting the flow of urine.

- Trouble emptying the bladder completely.

- Pain or burning while urinating.

- Blood in the urine or semen.

- A pain in the back, hips, or pelvis that doesn't go away.

- Shortness of breath, feeling very tired, fast heartbeat, dizziness, or pale skin caused by anemia.

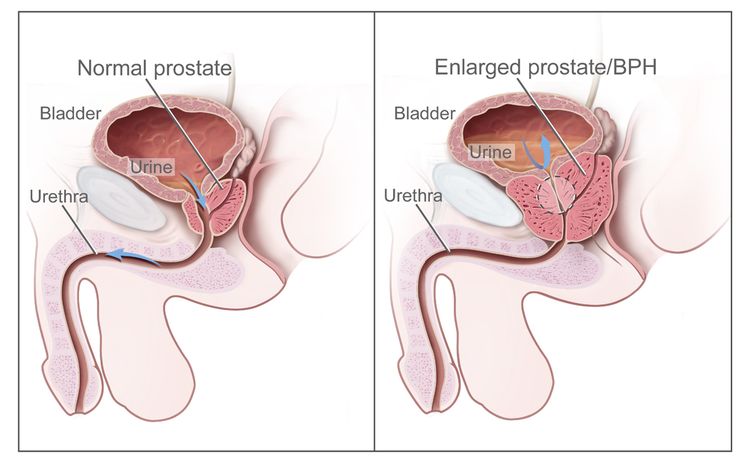

Other conditions may cause the same symptoms. As men age, the prostate may get bigger and block the urethra or bladder. This may cause trouble urinating or sexual problems. The condition is called benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and although it is not cancer, surgery may be needed. The symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia or of other problems in the prostate may be like symptoms of prostate cancer.

Tests that examine the prostate and blood are used to diagnose prostate cancer.

The following tests and procedures may be used:

- Physical exam and health history: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. A history of the patient’s health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken.

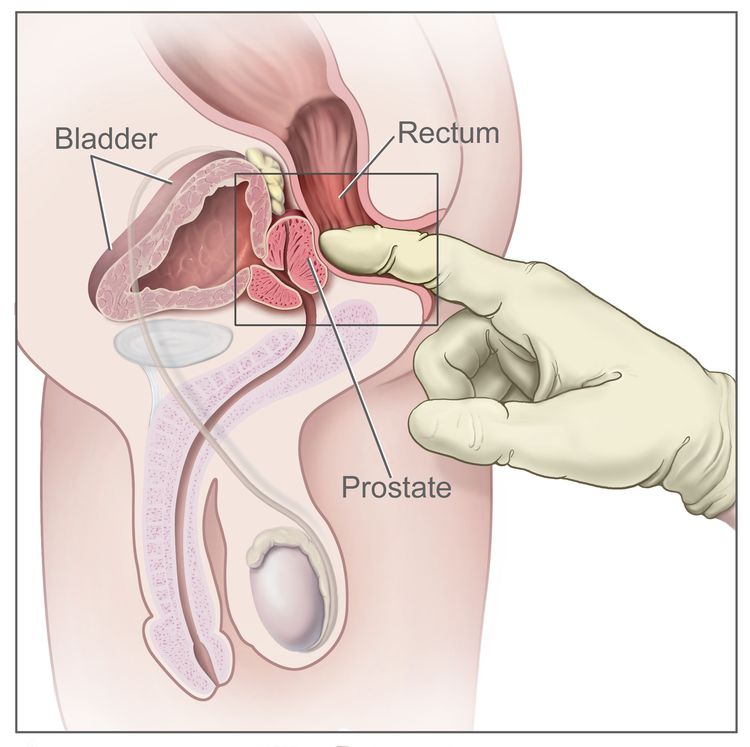

Digital rectal exam (DRE): An exam of the rectum. The doctor or nurse inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into the rectum and feels the prostate through the rectal wall for lumps or abnormal areas.

Digital rectal exam (DRE). The doctor inserts a gloved, lubricated finger into the rectum and feels the rectum, anus, and prostate (in males) to check for anything abnormal. - Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test: A test that measures the level of PSA in the blood. PSA is a substance made by the prostate that may be found in higher than normal amounts in the blood of men who have prostate cancer. PSA levels may also be high in men who have an infection or inflammation of the prostate or BPH (an enlarged, but noncancerous, prostate).

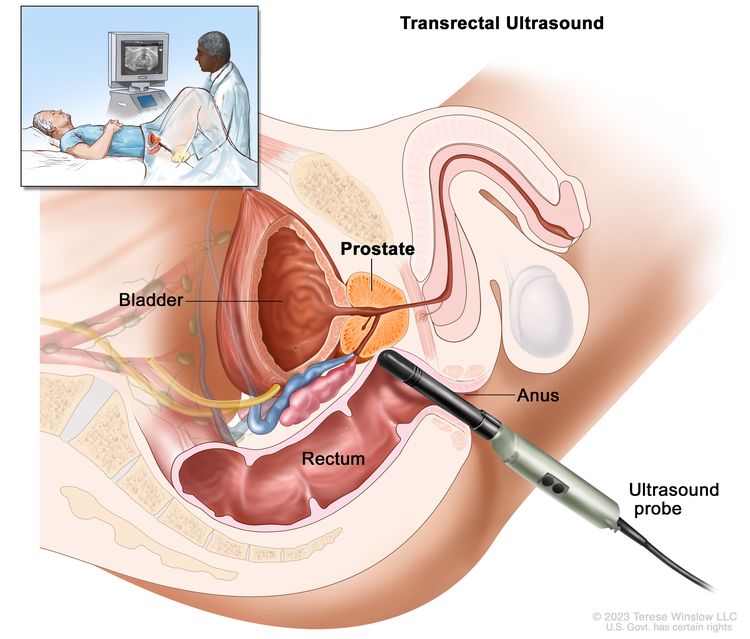

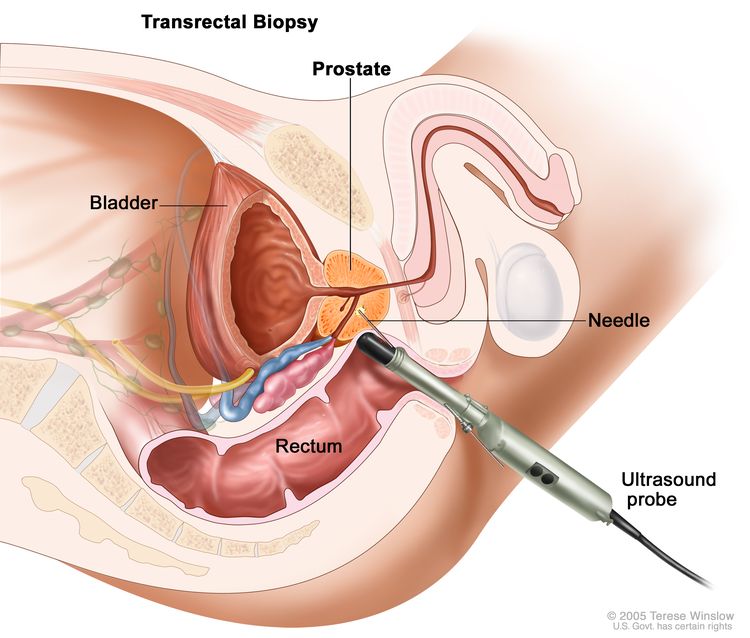

Transrectal ultrasound: A procedure in which a probe that is about the size of a finger is inserted into the rectum to check the prostate. The probe is used to bounce high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. Transrectal ultrasound may be used during a biopsy procedure. This is called transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy.

Transrectal ultrasound. An ultrasound probe is inserted into the rectum to check the prostate. The probe bounces sound waves off body tissues to make echoes that form a sonogram (computer picture) of the prostate. - Transrectal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): A procedure that uses a strong magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. A probe that gives off radio waves is inserted into the rectum near the prostate. This helps the MRI machine make clearer pictures of the prostate and nearby tissue. A transrectal MRI is done to find out if the cancer has spread outside the prostate into nearby tissues. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI). Transrectal MRI may be used during a biopsy procedure. This is called transrectal MRI guided biopsy.

A biopsy is done to diagnose prostate cancer and find out the grade of the cancer (Gleason score).

A transrectal biopsy is used to diagnose prostate cancer. A transrectal biopsy is the removal of tissue from the prostate by inserting a thin needle through the rectum and into the prostate. This procedure may be done using transrectal ultrasound or transrectal MRI to help guide where samples of tissue are taken from. A pathologist views the tissue under a microscope to look for cancer cells.

Sometimes a biopsy is done using a sample of tissue that was removed during a transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia.

If cancer is found, the pathologist will give the cancer a grade. The grade of the cancer describes how abnormal the cancer cells look under a microscope and how quickly the cancer is likely to grow and spread. The grade of the cancer is called the Gleason score.

To give the cancer a grade, the pathologist checks the prostate tissue samples to see how much the tumor tissue is like the normal prostate tissue and to find the two main cell patterns. The primary pattern describes the most common tissue pattern, and the secondary pattern describes the next most common pattern. Each pattern is given a grade from 3 to 5, with grade 3 looking the most like normal prostate tissue and grade 5 looking the most abnormal. The two grades are then added to get a Gleason score.

The Gleason score can range from 6 to 10. The higher the Gleason score, the more likely the cancer will grow and spread quickly. A Gleason score of 6 is a low-grade cancer; a score of 7 is a medium-grade cancer; and a score of 8, 9, or 10 is a high-grade cancer. For example, if the most common tissue pattern is grade 3 and the secondary pattern is grade 4, it means that most of the cancer is grade 3 and less of the cancer is grade 4. The grades are added for a Gleason score of 7, and it is a medium-grade cancer. The Gleason score may be written as 3+4=7, Gleason 7/10, or combined Gleason score of 7.

Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options.

The prognosis and treatment options depend on the following:

- The stage of the cancer (level of PSA, Gleason score, Grade Group, how much of the prostate is affected by the cancer, and whether the cancer has spread to other places in the body).

- The patient’s age.

- Whether the cancer has just been diagnosed or has recurred (come back).

Treatment options also may depend on the following:

- Whether the patient has other health problems.

- The expected side effects of treatment.

- Past treatment for prostate cancer.

- The wishes of the patient.

Most men diagnosed with prostate cancer do not die of it.

Stages of Prostate Cancer

Key Points

- After prostate cancer has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer cells have spread within the prostate or to other parts of the body.

- There are three ways that cancer spreads in the body.

- Cancer may spread from where it began to other parts of the body.

- The Grade Group and PSA level are used to stage prostate cancer.

- The following stages are used for prostate cancer:

- Prostate cancer may recur (come back) after it has been treated.

After prostate cancer has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer cells have spread within the prostate or to other parts of the body.

The process used to find out if cancer has spread within the prostate or to other parts of the body is called staging. The information gathered from the staging process determines the stage of the disease. It is important to know the stage in order to plan treatment. The results of the tests used to diagnose prostate cancer are often also used to stage the disease. (See the General Information section.) In prostate cancer, staging tests may not be done unless the patient has symptoms or signs that the cancer has spread, such as bone pain, a high PSA level, or a high Gleason score.

The following tests and procedures also may be used in the staging process:

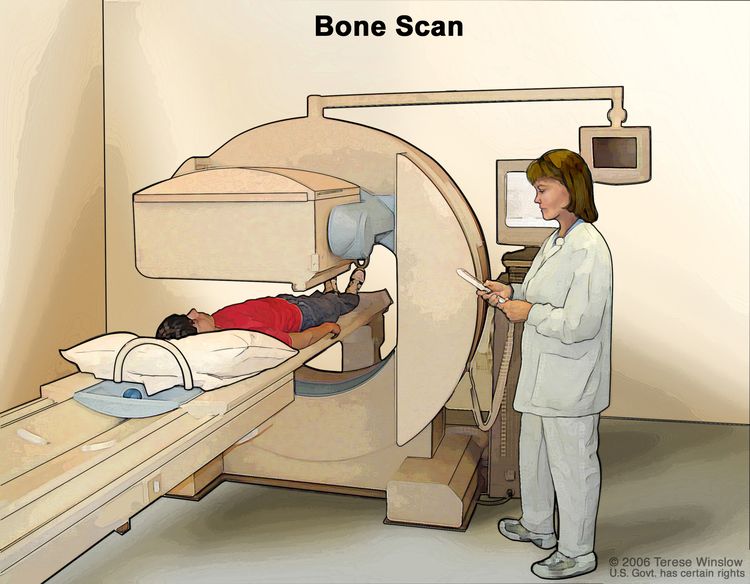

Bone scan: A procedure to check if there are rapidly dividing cells, such as cancer cells, in the bone. A very small amount of radioactive material is injected into a vein and travels through the bloodstream. The radioactive material collects in the bones with cancer and is detected by a scanner.

Bone scan. A small amount of radioactive material is injected into the patient's bloodstream and collects in abnormal cells in the bones. As the patient lies on a table that slides under the scanner, the radioactive material is detected and images are made on a computer screen or film. - MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): A procedure that uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI).

- CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

- Pelvic lymphadenectomy: A surgical procedure to remove the lymph nodes in the pelvis. A pathologist views the tissue under a microscope to look for cancer cells.

- Seminal vesicle biopsy: The removal of fluid from the seminal vesicles (glands that make semen) using a needle. A pathologist views the fluid under a microscope to look for cancer cells.

- ProstaScint scan: A procedure to check for cancer that has spread from the prostate to other parts of the body, such as the lymph nodes. A very small amount of radioactive material is injected into a vein and travels through the bloodstream. The radioactive material attaches to prostate cancer cells and is detected by a scanner. The radioactive material shows up as a bright spot on the picture in areas where there are a lot of prostate cancer cells.

There are three ways that cancer spreads in the body.

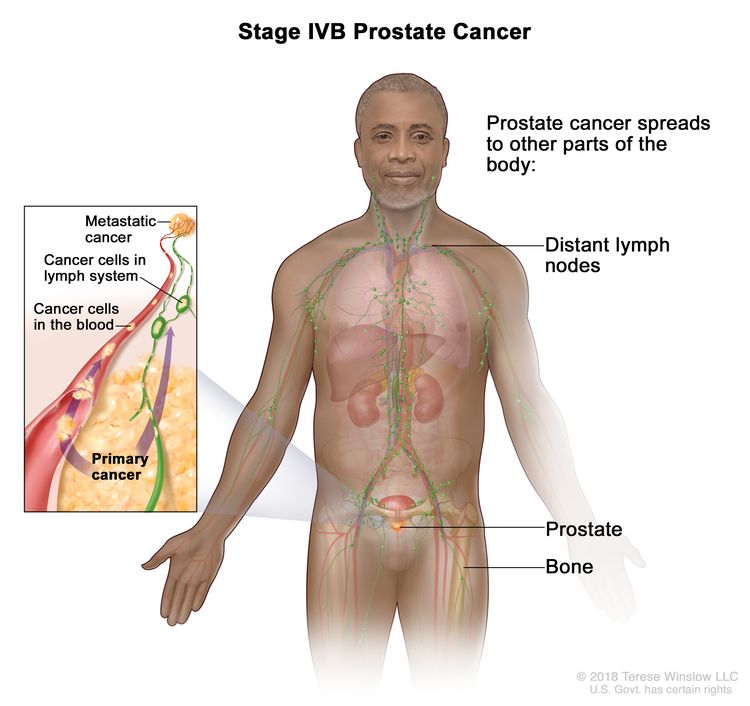

Cancer can spread through tissue, the lymph system, and the blood:

- Tissue. The cancer spreads from where it began by growing into nearby areas.

- Lymph system. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the lymph system. The cancer travels through the lymph vessels to other parts of the body.

- Blood. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the blood. The cancer travels through the blood vessels to other parts of the body.

Cancer may spread from where it began to other parts of the body.

When cancer spreads to another part of the body, it is called metastasis. Cancer cells break away from where they began (the primary tumor) and travel through the lymph system or blood.

- Lymph system. The cancer gets into the lymph system, travels through the lymph vessels, and forms a tumor (metastatic tumor) in another part of the body.

- Blood. The cancer gets into the blood, travels through the blood vessels, and forms a tumor (metastatic tumor) in another part of the body.

The metastatic tumor is the same type of cancer as the primary tumor. For example, if prostate cancer spreads to the bone, the cancer cells in the bone are actually prostate cancer cells. The disease is metastatic prostate cancer, not bone cancer.

Denosumab, a monoclonal antibody, may be used to prevent bone metastases.

The Grade Group and PSA level are used to stage prostate cancer.

The stage of the cancer is based on the results of the staging and diagnostic tests, including the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and the Grade Group. The tissue samples removed during the biopsy are used to find out the Gleason score. The Gleason score ranges from 2 to 10 and describes how different the cancer cells look from normal cells under a microscope and how likely it is that the tumor will spread. The lower the number, the more cancer cells look like normal cells and are likely to grow and spread slowly.

The Grade Group depends on the Gleason score. See the General Information section for more information about the Gleason score.

- Grade Group 1 is a Gleason score of 6 or less.

- Grade Group 2 or 3 is a Gleason score of 7.

- Grade Group 4 is a Gleason score 8.

- Grade Group 5 is a Gleason score of 9 or 10.

The PSA test measures the level of PSA in the blood. PSA is a substance made by the prostate that may be found in an increased amount in the blood of men who have prostate cancer.

The following stages are used for prostate cancer:

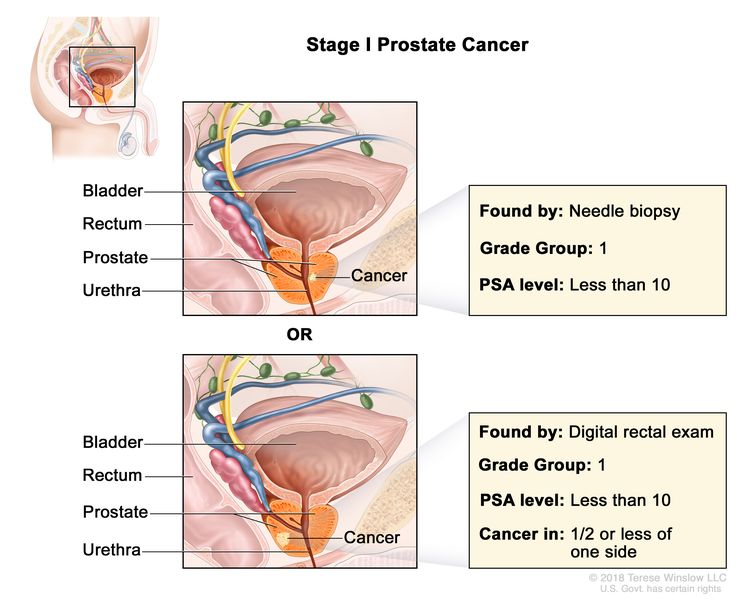

Stage I

In stage I, cancer is found in the prostate only. The cancer:

- is not felt during a digital rectal exam and is found by needle biopsy (done for a high PSA level) or in a sample of tissue removed during surgery for other reasons (such as benign prostatic hyperplasia). The PSA level is lower than 10 and the Grade Group is 1; or

- is felt during a digital rectal exam and is found in one-half or less of one side of the prostate. The PSA level is lower than 10 and the Grade Group is 1.

Stage I

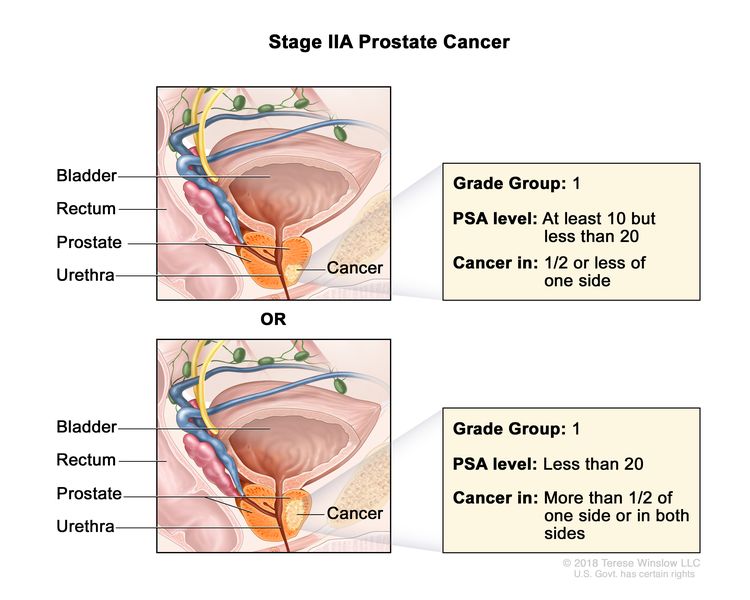

In stage II, cancer is more advanced than in stage I, but has not spread outside the prostate. Stage II is divided into stages IIA, IIB, and IIC.

In stage IIA, cancer:

- is found in one-half or less of one side of the prostate. The PSA level is at least 10 but lower than 20 and the Grade Group is 1; or

- is found in more than one-half of one side of the prostate or in both sides of the prostate. The PSA level is lower than 20 and the Grade Group is 1.

In stage IIB, cancer:

- is found in one or both sides of the prostate. The PSA level is lower than 20 and the Grade Group is 2.

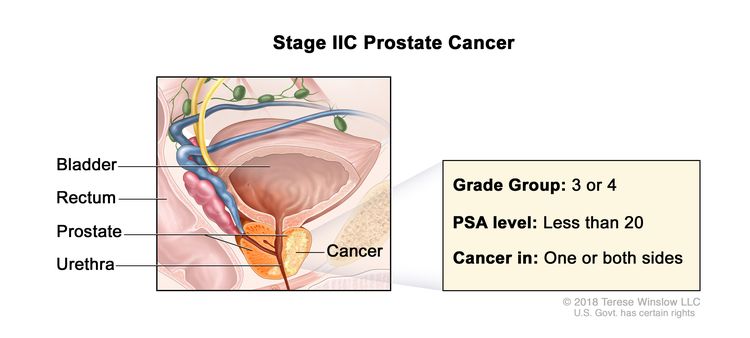

In stage IIC, cancer:

- is found in one or both sides of the prostate. The PSA level is lower than 20 and the Grade Group is 3 or 4.

Stage I

Stage III is divided into stages IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC.

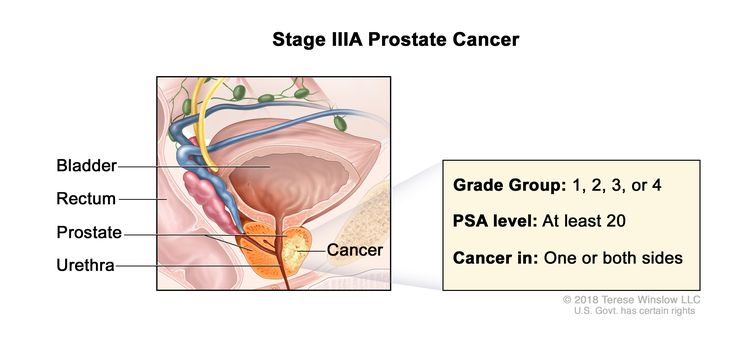

In stage IIIA, cancer:

- is found in one or both sides of the prostate. The PSA level is at least 20 and the Grade Group is 1, 2, 3, or 4.

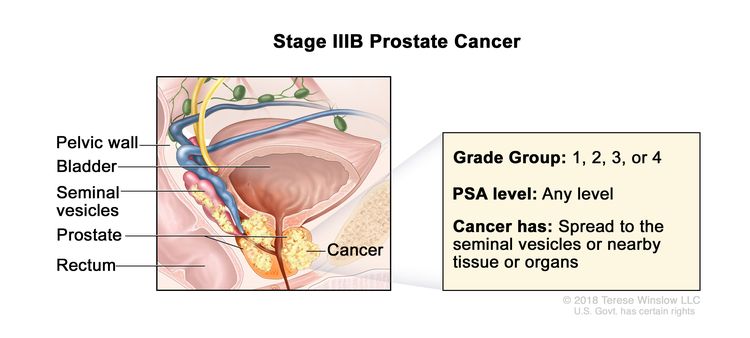

In stage IIIB, cancer:

- has spread from the prostate to the seminal vesicles or to nearby tissue or organs, such as the rectum, bladder, or pelvic wall. The PSA can be any level and the Grade Group is 1, 2, 3, or 4.

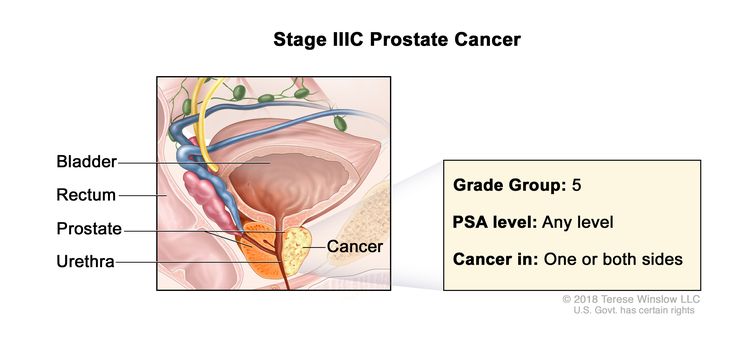

In stage IIIC, cancer:

- is found in one or both sides of the prostate and may have spread to the seminal vesicles or to nearby tissue or organs, such as the rectum, bladder, or pelvic wall. The PSA can be any level and the Grade Group is 5.

Stage I

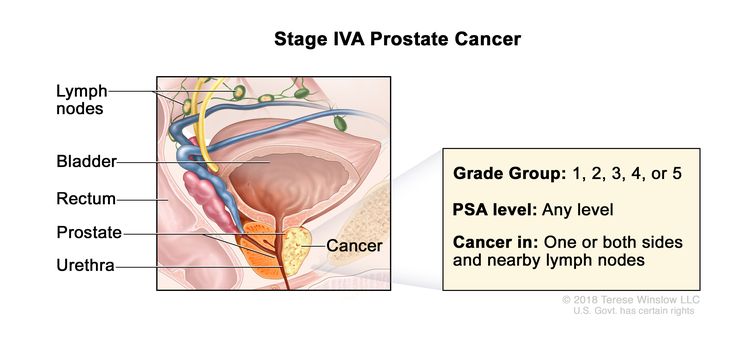

Stage IV is divided into stages IVA and IVB.

In stage IVA, cancer:

- is found in one or both sides of the prostate and may have spread to the seminal vesicles or to nearby tissue or organs, such as the rectum, bladder, or pelvic wall. Cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes. The PSA can be any level and the Grade Group is 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5.

In stage IVB, cancer:

- has spread to other parts of the body, such as the bones or distant lymph nodes. Prostate cancer often spreads to the bones.

Prostate cancer may recur (come back) after it has been treated.

The cancer may come back in the prostate or in other parts of the body.

Treatment Option Overview

Key Points

- There are different types of treatment for patients with prostate cancer.

- Eight types of standard treatment are used:

- There are treatments for bone pain caused by bone metastases or hormone therapy.

- New types of treatment are being tested in clinical trials.

- Cryosurgery

- High-intensity–focused ultrasound therapy

- Proton beam radiation therapy

- Photodynamic therapy

- Treatment for prostate cancer may cause side effects.

- Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial.

- Patients can enter clinical trials before, during, or after starting their cancer treatment.

- Follow-up tests may be needed.

There are different types of treatment for patients with prostate cancer.

Different types of treatment are available for patients with prostate cancer. Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being tested in clinical trials. A treatment clinical trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials show that a new treatment is better than the standard treatment, the new treatment may become the standard treatment. Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Eight types of standard treatment are used:

Watchful waiting or active surveillance

Watchful waiting and active surveillance are treatments used for older men who do not have signs or symptoms or have other medical conditions and for men whose prostate cancer is found during a screening test.

Watchful waiting is closely monitoring a patient’s condition without giving any treatment until signs or symptoms appear or change. Treatment is given to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life.

Active surveillance is closely following a patient's condition without giving any treatment unless there are changes in test results. It is used to find early signs that the condition is getting worse. In active surveillance, patients are given certain exams and tests, including digital rectal exam, PSA test, transrectal ultrasound, and transrectal needle biopsy, to check if the cancer is growing. When the cancer begins to grow, treatment is given to cure the cancer.

Other terms that are used to describe not giving treatment to cure prostate cancer right after diagnosis are observation, watch and wait, and expectant management.

Surgery

Patients in good health whose tumor is in the prostate gland only may be treated with surgery to remove the tumor. The following types of surgery are used:

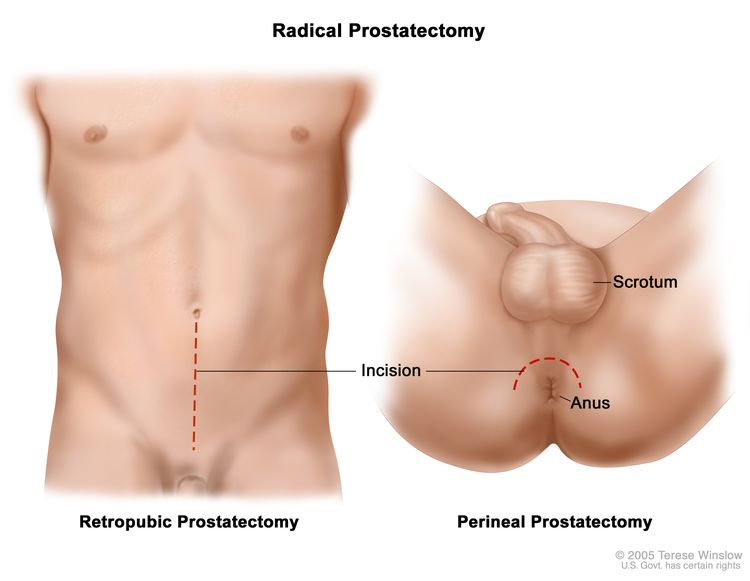

Radical prostatectomy: A surgical procedure to remove the prostate, surrounding tissue, and seminal vesicles. Removal of nearby lymph nodes may be done at the same time. The main types of radical prostatectomy include:

- Open radical prostatectomy: An incision (cut) is made in the retropubic area (lower abdomen) or the perineum (the area between the anus and scrotum). Surgery is performed through the incision. It is harder for the surgeon to spare the nerves near the prostate or to remove nearby lymph nodes with the perineum approach.

- Radical laparoscopic prostatectomy: Several small incisions (cuts) are made in the wall of the abdomen. A laparoscope (a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and lens for viewing) is inserted through one opening to guide the surgery. Surgical instruments are inserted through the other openings to do the surgery.

- Robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: Several small cuts are made in the wall of the abdomen, as in regular laparoscopic prostatectomy. The surgeon inserts an instrument with a camera through one of the openings and surgical instruments through the other openings using robotic arms. The camera gives the surgeon a 3-dimensional view of the prostate and surrounding structures. The surgeon uses the robotic arms to do the surgery while sitting at a computer monitor near the operating table.

Two types of radical prostatectomy. In a retropubic prostatectomy, the prostate is removed through an incision in the wall of the abdomen. In a perineal prostatectomy, the prostate is removed through an incision in the area between the scrotum and the anus. - Pelvic lymphadenectomy: A surgical procedure to remove the lymph nodes in the pelvis. A pathologist views the tissue under a microscope to look for cancer cells. If the lymph nodes contain cancer, the doctor will not remove the prostate and may recommend other treatment.

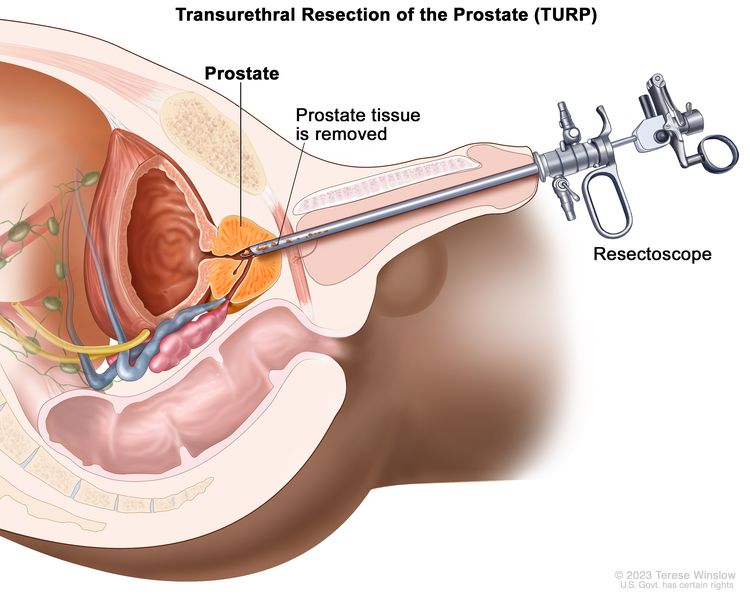

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP): A surgical procedure to remove tissue from the prostate using a resectoscope (a thin, lighted tube with a cutting tool) inserted through the urethra. This procedure is done to treat benign prostatic hypertrophy and it is sometimes done to relieve symptoms caused by a tumor before other cancer treatment is given. TURP may also be done in men whose tumor is in the prostate only and who cannot have a radical prostatectomy.

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). Tissue is removed from the prostate using a resectoscope (a thin, lighted tube with a cutting tool at the end) inserted through the urethra. Prostate tissue that is blocking the urethra is cut away and removed through the resectoscope.

In some cases, the nerves that control penile erection can be saved with nerve-sparing surgery. However, this may not be possible in men with large tumors or tumors that are very close to the nerves.

Possible problems after prostate cancer surgery include the following:

- Impotence.

- Leakage of urine from the bladder or stool from the rectum.

- Shortening of the penis (1 to 2 centimeters). The exact reason for this is not known.

- Inguinal hernia (bulging of fat or part of the small intestine through weak muscles into the groin). Inguinal hernia may occur more often in men treated with radical prostatectomy than in men who have some other types of prostate surgery, radiation therapy, or prostate biopsy alone. It is most likely to occur within the first 2 years after radical prostatectomy.

Radiation therapy and radiopharmaceutical therapy

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. There are different types of radiation therapy:

External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the area of the body with cancer. Conformal radiation is a type of external radiation therapy that uses a computer to make a 3-dimensional (3-D) picture of the tumor and shapes the radiation beams to fit the tumor. This allows a high dose of radiation to reach the tumor and causes less damage to nearby healthy tissue.

Hypofractionated radiation therapy may be given because it has a more convenient treatment schedule. Hypofractionated radiation therapy is radiation treatment in which a larger than usual total dose of radiation is given once a day over a shorter period of time (fewer days) compared to standard radiation therapy. Hypofractionated radiation therapy may have worse side effects than standard radiation therapy, depending on the schedules used.

- Internal radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance sealed in needles, seeds, wires, or catheters that are placed directly into or near the cancer. In early-stage prostate cancer, the radioactive seeds are placed in the prostate using needles that are inserted through the skin between the scrotum and rectum. The placement of the radioactive seeds in the prostate is guided by images from transrectal ultrasound or computed tomography (CT). The needles are removed after the radioactive seeds are placed in the prostate.

Radiopharmaceutical therapy uses a radioactive substance to treat cancer. Radiopharmaceutical therapy includes the following:

- Alpha emitter radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance to treat prostate cancer that has spread to the bone. A radioactive substance called radium-223 is injected into a vein and travels through the bloodstream. The radium-223 collects in areas of bone with cancer and kills the cancer cells.

The way the radiation therapy is given depends on the type and stage of the cancer being treated. External radiation therapy, internal radiation therapy, and radiopharmaceutical therapy are used to treat prostate cancer.

Men treated with radiation therapy for prostate cancer have an increased risk of having bladder and/or gastrointestinal cancer.

Radiation therapy can cause impotence and urinary problems that may get worse with age.

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy is a cancer treatment that removes hormones or blocks their action and stops cancer cells from growing. Hormones are substances made by glands in the body and circulated in the bloodstream. In prostate cancer, male sex hormones can cause prostate cancer to grow. Drugs, surgery, or other hormones are used to reduce the amount of male hormones or block them from working. This is called androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).

Hormone therapy for prostate cancer may include the following:

- Abiraterone acetate can prevent prostate cancer cells from making androgens. It is used in men with advanced prostate cancer that has not gotten better with other hormone therapy. It is also used in men with high-risk prostate cancer that has improved with treatments that lower hormone levels.

- Orchiectomy is a surgical procedure to remove one or both testicles, the main source of male hormones, such as testosterone, to decrease the amount of hormone being made.

- Estrogens (hormones that promote female sex characteristics) can prevent the testicles from making testosterone. However, estrogens are seldom used today in the treatment of prostate cancer because of the risk of serious side effects.

- Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists can stop the testicles from making testosterone. Examples are leuprolide, goserelin, and buserelin.

- Antiandrogens can block the action of androgens (hormones that promote male sex characteristics), such as testosterone. Examples are flutamide, bicalutamide, enzalutamide, apalutamide, nilutamide, and darolutamide.

- Drugs that can prevent the adrenal glands from making androgens include ketoconazole, aminoglutethimide, hydrocortisone, and progesterone.

Hot flashes, impaired sexual function, loss of desire for sex, and weakened bones may occur in men treated with hormone therapy. Other side effects include diarrhea, nausea, and itching.

See Drugs Approved for Prostate Cancer for more information.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a cancer treatment that uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping them from dividing. When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein or muscle, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body (systemic chemotherapy).

See Drugs Approved for Prostate Cancer for more information.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a type of treatment that uses drugs or other substances to identify and attack specific cancer cells. Targeted therapies usually cause less harm to normal cells than chemotherapy or radiation therapy do.

- PARP inhibitors block an enzyme involved in many cell functions, including the repair of DNA damage. Blocking this enzyme may help keep cancer cells from repairing their damaged DNA, causing them to die. Olaparib is a PARP inhibitor used to treat patients with prostate cancer that has spread to other parts of the body and has mutations in certain genes, such as BRCA1 or BRCA2.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a treatment that uses the patient’s immune system to fight cancer. Substances made by the body or made in a laboratory are used to boost, direct, or restore the body’s natural defenses against cancer. This cancer treatment is a type of biologic therapy. Sipuleucel-T is a type of immunotherapy used to treat prostate cancer that has metastasized (spread to other parts of the body).

See Drugs Approved for Prostate Cancer for more information.

Bisphosphonate therapy

Bisphosphonate drugs, such as clodronate or zoledronate, reduce bone disease when cancer has spread to the bone. Men who are treated with antiandrogen therapy or orchiectomy are at an increased risk of bone loss. In these men, bisphosphonate drugs lessen the risk of bone fracture (breaks). The use of bisphosphonate drugs to prevent or slow the growth of bone metastases is being studied in clinical trials.

There are treatments for bone pain caused by bone metastases or hormone therapy.

Prostate cancer that has spread to the bone and certain types of hormone therapy can weaken bones and lead to bone pain. Treatments for bone pain include the following:

- Pain medicine.

- External radiation therapy.

- Strontium-89 (a radioisotope).

- Targeted therapy with a monoclonal antibody, such as denosumab.

- Bisphosphonate therapy

- Corticosteroids.

New types of treatment are being tested in clinical trials.

This summary section describes treatments that are being studied in clinical trials. It may not mention every new treatment being studied. Information about clinical trials is available from the NCI website.

Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery is a treatment that uses an instrument to freeze and destroy prostate cancer cells. Ultrasound is used to find the area that will be treated. This type of treatment is also called cryotherapy.

Cryosurgery can cause impotence and leakage of urine from the bladder or stool from the rectum.

High-intensity–focused ultrasound therapy

High-intensity–focused ultrasound therapy is a treatment that uses ultrasound (high-energy sound waves) to destroy cancer cells. To treat prostate cancer, an endorectal probe is used to make the sound waves.

Proton beam radiation therapy

Proton beam radiation therapy is a type of high-energy, external radiation therapy that uses streams of protons (tiny particles with a positive charge) to kill tumor cells. This type of treatment can lower the amount of radiation damage to healthy tissue near a tumor.

Photodynamic therapy

A cancer treatment that uses a drug and a certain type of laser light to kill cancer cells. A drug that is not active until it is exposed to light is injected into a vein. The drug collects more in cancer cells than in normal cells. Fiberoptic tubes are then used to carry the laser light to the cancer cells, where the drug becomes active and kills the cells. Photodynamic therapy causes little damage to healthy tissue. It is used mainly to treat tumors on or just under the skin or in the lining of internal organs.

Treatment for prostate cancer may cause side effects.

For information about side effects caused by treatment for cancer, see our Side Effects page.

Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial.

For some patients, taking part in a clinical trial may be the best treatment choice. Clinical trials are part of the cancer research process. Clinical trials are done to find out if new cancer treatments are safe and effective or better than the standard treatment.

Many of today's standard treatments for cancer are based on earlier clinical trials. Patients who take part in a clinical trial may receive the standard treatment or be among the first to receive a new treatment.

Patients who take part in clinical trials also help improve the way cancer will be treated in the future. Even when clinical trials do not lead to effective new treatments, they often answer important questions and help move research forward.

Patients can enter clinical trials before, during, or after starting their cancer treatment.

Some clinical trials only include patients who have not yet received treatment. Other trials test treatments for patients whose cancer has not gotten better. There are also clinical trials that test new ways to stop cancer from recurring (coming back) or reduce the side effects of cancer treatment.

Clinical trials are taking place in many parts of the country. Information about clinical trials supported by NCI can be found on NCI’s clinical trials search webpage. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Follow-up tests may be needed.

Some of the tests that were done to diagnose the cancer or to find out the stage of the cancer may be repeated. Some tests will be repeated in order to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Some of the tests will continue to be done from time to time after treatment has ended. The results of these tests can show if your condition has changed or if the cancer has recurred (come back). These tests are sometimes called follow-up tests or check-ups.

Treatment of Stage I Prostate Cancer

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Standard treatment of stage I prostate cancer may include the following:

- Watchful waiting.

- Active surveillance. If the cancer begins to grow, hormone therapy may be given.

- Radical prostatectomy, usually with pelvic lymphadenectomy. Radiation therapy may be given after surgery.

- External radiation therapy. Hormone therapy may be given after radiation therapy.

- Internal radiation therapy with radioactive seeds.

- A clinical trial of high-intensity–focused ultrasound therapy.

- A clinical trial of photodynamic therapy.

- A clinical trial of cryosurgery.

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. General information about clinical trials is also available.

Treatment of Stage II Prostate Cancer

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Standard treatment of stage II prostate cancer may include the following:

- Watchful waiting.

- Active surveillance. If the cancer begins to grow, hormone therapy may be given.

- Radical prostatectomy, usually with pelvic lymphadenectomy. Radiation therapy may be given after surgery.

- External radiation therapy. Hormone therapy may be given after radiation therapy.

- Internal radiation therapy with radioactive seeds.

- A clinical trial of cryosurgery.

- A clinical trial of high-intensity–focused ultrasound therapy.

- A clinical trial of proton beam radiation therapy.

- A clinical trial of photodynamic therapy.

- Clinical trials of new types of treatment, such as hormone therapy followed by radical prostatectomy.

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. General information about clinical trials is also available.

Treatment of Stage III Prostate Cancer

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Standard treatment of stage III prostate cancer may include the following:

- External radiation therapy. Hormone therapy may be given after radiation therapy.

- Hormone therapy

- Radical prostatectomy. Radiation therapy may be given after surgery.

- Watchful waiting.

- Active surveillance. If the cancer begins to grow, hormone therapy may be given.

Treatment to control cancer that is in the prostate and lessen urinary symptoms may include the following:

- External radiation therapy.

- Internal radiation therapy with radioactive seeds.

- Hormone therapy

- Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).

- A clinical trial of new types of radiation therapy.

- A clinical trial of cryosurgery.

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. General information about clinical trials is also available.

Treatment of Stage IV Prostate Cancer

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Standard treatment of stage IV prostate cancer may include the following:

- Hormone therapy.

- Hormone therapy

- Bisphosphonate therapy.

- External radiation therapy. Hormone therapy may be given after radiation therapy.

- Alpha emitter radiation therapy.

- Watchful waiting.

- Active surveillance. If the cancer begins to grow, hormone therapy may be given.

- A clinical trial of radical prostatectomy with orchiectomy.

Treatment to control cancer that is in the prostate and lessen urinary symptoms may include the following:

- Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).

- Radiation therapy.

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. General information about clinical trials is also available.

Treatment of Recurrent or Hormone-Resistant Prostate Cancer

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Standard treatment of recurrent or hormone-resistant prostate cancer may include the following:

- Hormone therapy.

- Chemotherapy for patients already treated with hormone therapy.

- Biologic therapy with sipuleucel-T for patients already treated with hormone therapy.

- External radiation therapy.

- Prostatectomy for patients already treated with radiation therapy.

- Alpha emitter radiation therapy.

- PARP inhibitor therapy for patients already treated with hormone therapy who have mutations in certain genes, such as BRCA1 or BRCA2.

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. General information about clinical trials is also available.

To Learn More About Prostate Cancer

For more information from the National Cancer Institute about prostate cancer, see the following:

- Prostate Cancer Home Page

- Prostate Cancer, Nutrition, and Dietary Supplements

- Prostate Cancer Prevention

- Prostate Cancer Screening

- Drugs Approved for Prostate Cancer

- Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Test

- Hormone Therapy for Prostate Cancer

- Targeted Cancer Therapies

- Immunotherapy to Treat Cancer

- Treatment Choices for Men with Early-Stage Prostate Cancer

- Cryosurgery to Treat Cancer

For general cancer information and other resources from the National Cancer Institute, see the following:

About This PDQ Summary

About PDQ

Physician Data Query (PDQ) is the National Cancer Institute's (NCI's) comprehensive cancer information database. The PDQ database contains summaries of the latest published information on cancer prevention, detection, genetics, treatment, supportive care, and complementary and alternative medicine. Most summaries come in two versions. The health professional versions have detailed information written in technical language. The patient versions are written in easy-to-understand, nontechnical language. Both versions have cancer information that is accurate and up to date and most versions are also available in Spanish.

PDQ is a service of the NCI. The NCI is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH is the federal government’s center of biomedical research. The PDQ summaries are based on an independent review of the medical literature. They are not policy statements of the NCI or the NIH.

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary has current information about the treatment of prostate cancer. It is meant to inform and help patients, families, and caregivers. It does not give formal guidelines or recommendations for making decisions about health care.

Reviewers and Updates

Editorial Boards write the PDQ cancer information summaries and keep them up to date. These Boards are made up of experts in cancer treatment and other specialties related to cancer. The summaries are reviewed regularly and changes are made when there is new information. The date on each summary ("Updated") is the date of the most recent change.

The information in this patient summary was taken from the health professional version, which is reviewed regularly and updated as needed, by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board.

Clinical Trial Information

A clinical trial is a study to answer a scientific question, such as whether one treatment is better than another. Trials are based on past studies and what has been learned in the laboratory. Each trial answers certain scientific questions in order to find new and better ways to help cancer patients. During treatment clinical trials, information is collected about the effects of a new treatment and how well it works. If a clinical trial shows that a new treatment is better than one currently being used, the new treatment may become "standard." Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Clinical trials can be found online at NCI's website. For more information, call the Cancer Information Service (CIS), NCI's contact center, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. The content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text. It cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless the whole summary is shown and it is updated regularly. However, a user would be allowed to write a sentence such as “NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks in the following way: [include excerpt from the summary].”

The best way to cite this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Prostate Cancer Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389353]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use in the PDQ summaries only. If you want to use an image from a PDQ summary and you are not using the whole summary, you must get permission from the owner. It cannot be given by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the images in this summary, along with many other images related to cancer can be found in Visuals Online. Visuals Online is a collection of more than 3,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used to make decisions about insurance reimbursement. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website’s E-mail Us.

Updated:

This content is provided by the National Cancer Institute (www.cancer.gov)

Source URL: https://www.cancer.gov/node/4328/syndication

Source Agency: National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Captured Date: 2013-09-14 09:02:09.0